THE CASE OF THE UNCERTAIN INVESTOR

RISK MANAGEMENT AND SPENDING GOALS

FROM THE BLEACHERS, VOL. 21

MARKET UPDATE

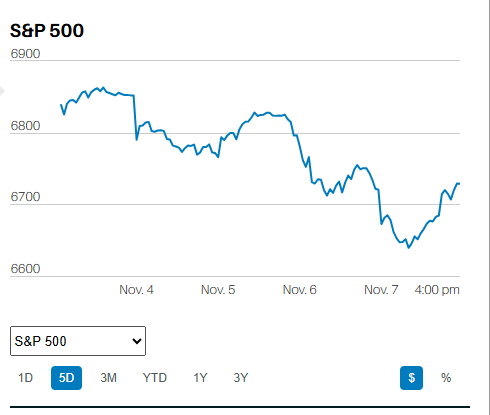

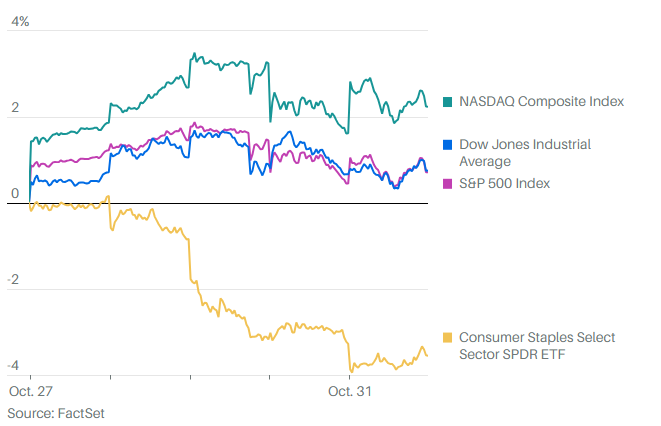

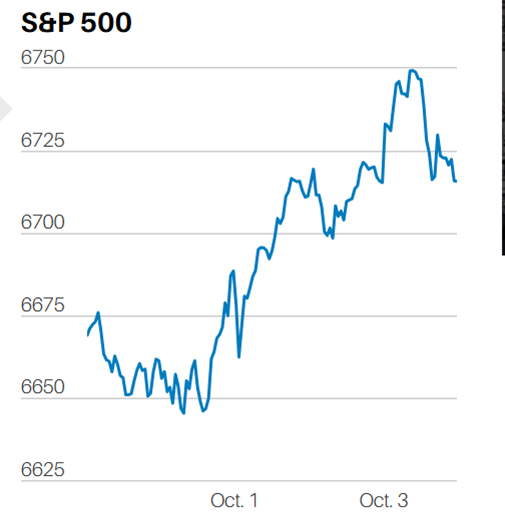

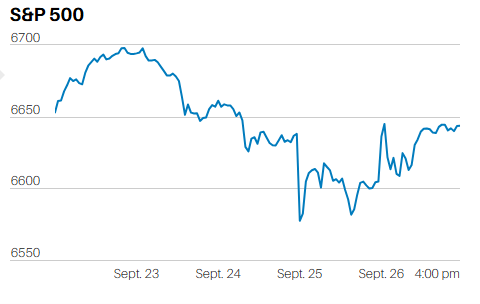

The Dow Jones Industrial average fell for the fifth week in a row, dropping 0.7% on the week. The S&P 500 fell 1.2% to 2826.06. The index hit a high of 2872.87 on 1/26/2018 before selling off sharply to a low of 2532 just a few weeks later. The index eventually went on to a high of 2941 on 9/21/2019 before falling almost 20% to a low of 2346 on 12/26/18. The S&P 500 rebounded strongly to a new all-time high of 2954 on 5/1/2019, only to fail to take the 3,000 level, instead falling back to the most recent low of 2801.

The importance of recounting the S&P 500 index movements over the last 17 months is to highlight the fact that the stock market action currently is still indistinguishable from the topping action frequently seen before a bear market. It is true that the S&P 500 is up 12.8% year-to-date in 2019. It is also true that the index is down 1.6% over the last 17 months. Furthermore, the economic data continues to paint a picture that is less than rosy, but still not necessarily predictive of a recession (although we still think a recession later this year or early next is a strong possibility – say a 60% to 70% chance).

The price of copper is dropping as is crude oil. There are other factors that can impact the price of both, but slowing demand due to a slowing world economy is high on the list of likely reasons. The Treasury yield curve is inverted once again, with the two-year finishing the week at 2.37% and the ten-year at 2.32%. The inversion is a further indication that the bond market doesn’t expect inflation anytime soon, which also means the bond market isn’t expecting economic growth to accelerate in the near future. An inverted yield curve is problematic for banks since they’re in the business of borrowing at short-term rates and lending at (normally) higher long-term rates. Banks reduce lending when they can’t make money on it. An inverted yield curve is also highly predictive of a recession (typically within 12 to 18 months of the initial inversion) in part because of the slowing in credit growth. As well, there is now $10.6 trillion in negative yielding debt worldwide, double the amount in October. Remember, negative yielding debt was thought to be impossible just a short decade ago, something that hadn’t happened in 4,000 years of recorded history. Negative yielding debt is exhibit A for making the case that there is still something very wrong with the world economy, despite the last ten years of economic expansion.

Meanwhile, the IHS Markit Purchasing Managers Index dropped to just above 50, which is the line between expansion and contraction. Also, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow index is forecasting 1.3% annualized growth in the current quarter, down from 2018’s 3.2% real GDP growth. As well, the Weekly Leading Index of the Economic Cycle Research Institute (ECRI) has fallen to levels that indicate slow to no growth in coming quarters.

Our conclusion remains the same as it’s been since last December’s market bottom. The current bounce that began on 26 December may be a renewal of the 10-year bull market, but it is at least as likely part of a normal topping process that will eventually lead to new lows as the stock market anticipates a recession later this year or early in 2020. Caveat Emptor!

THE UNCERTAIN INVESTOR

So what’s an investor to do when confronted with the highly likely possibility of a bear market sometime in the next year or two? I was asked this question during a 401(k) annual review last week.

Stay fully invested in your current asset allocation if your spending goals won’t be impacted by the next bear market. Practice risk management if your spending goals will be impacted by the next bear market. Risk management is distinct from market timing. Risk management is looking at your portfolio and making a determination of whether a 30% to 50% decline in the stock market will force you to change your spending plans, including your retirement date. If not, make no changes. If a bear market might force you to make adjustments in your spending, then make changes to your asset allocation to reduce the risk of a disruption in your spending plans.

Risk management is a math problem that requires you to first identify your spending plans, add up your investable assets and likely additional savings, and then run some calculations. We use a program called MoneyGuidePro that allows us to build detailed models for our clients. We’re able to do scenario analysis, changing one variable at a time to see how the change impacts the probability of successfully funding all of their spending goals on time and in full. What does the probability of success look like with this retirement date or with that retirement date? What does a $5,000 annual travel budget do to the probability of success? A $10,000 annual travel budget? How about a 3% average annual return between now and retirement? A 6% average annual return? Financial planning allows you to make better decisions about risk management, a particularly important undertaking when capital market uncertainty is high, as it is now.

Many 401(k) plan websites have retirement calculators that, while perhaps not as sophisticated as MoneyGuidePro, are able to give you some idea of what a (for instance) five-year period of flat returns might do to your spending plans, including your retirement date. You may also want to look at flat returns over the next ten years as well. Many of the metrics we use for 10-year expected returns are pointing toward low single digits as the likely return for the S&P 500 during the next decade. What might that do to your spending plans, including your retirement date? If it were me, I’d want to know.

Regards,

Christopher R Norwood, CFA

Chief Market Strategist