ECONOMICS AS NARRATIVE

Economics is not a hard science in the tradition of physics, chemistry, or even biology. It is a soft science (at best) more comparable with sociology or psychology. Importantly, because the study of economics is largely about how to most efficiently use limited resources, it is all too often joined at the hip with politics (the process of allocating scarce resources among a population).

Importantly, because the study of economics is largely about how to most efficiently use limited resources, it is all too often joined at the hip with politics (the process of allocating scarce resources among a population). Consequently, economics all too often serves as narrative for some politically predetermined goal(s). Bad data, ignorance of universal and universally consistent causalities, incomplete knowledge of people as economic agents, a lack of a unifying theory of economics that actually works in real economic space… our economic ignorance is grand! Yet the professors of the Federal Reserve believe they can end Quantitative Easing (an ill-conceived monetary policy tool in its own right) without so much as a hiccup in the world economy, the U.S. economy, and the capital markets. We should not hold our collective breath…

Economics as Narrative

The second law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of an isolated system never decreases. Put another way, all energy exchanges occurring in an isolated system result in less energy available to do work after each successive energy exchange. Got that? Not really? No worries. I am a little fuzzy on all of the many ramifications of the second law myself, although I do get that it is tremendously important to our understanding of all sorts of things in the real world in which we live.

For instance, the Second Law explains why my teenage daughter’s bedroom becomes increasingly chaotic (disorganized) after its once per month (maybe?) cleaning. Energy is introduced into what is otherwise an isolated system (as in “No Trespassing Keep Out”) when her room gets tidied up from time to time. However the room almost immediately begins to experience an increase in entropy as order slowly and inevitably disintegrates into the kind of mess that teenagers seem to come by naturally.

But the real point here is that the Laws of Thermodynamics are absolute, unchanging, and unbreakable. Physicists, to a man and woman, accept the three laws of Thermodynamics as fact, in large part because Physics is a hard science (producing testable predictions; performing controlled experiments; relying on quantifiable data and mathematical models; a high degree of accuracy and objectivity; and generally applying a purer form of the scientific method, according to Wikipedia) All of which means that physicists accept the three laws as fact because the evidence is overwhelming and conclusive.

Economists on the other hand…well…they tend to tell stories, narratives that often conflict…

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was shared in 2013 by three American economists for at times conflicting research on how financial markets work and assets such as stocks are priced, writes Rich Miller of Bloomberg. “The winners represent a very interesting collection because Fama is the founder of the efficient-market theory and Shiller at least is one of the critics of it,” said Robert Solow, winner of the Nobel Economics prize in 1987. “It’s like giving a prize to the Yankees and the Red Sox,” he said in the Bloomberg interview, comparing the competing theories to the rivalry between the New York and Boston baseball teams. “What is suggests is there really isn’t a settled doctrine in finance”

Really?

Keynesian economics dominates the policy choices of the Federal Reserve. “Keynesian economists often argue that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes which require active policy responses by the public sector, in particular, monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government, in order to stabilize output over the business cycle. Keynesian economics advocates a mixed economy – predominantly private sector, but with a role for government intervention during recessions,” Wikipedia.

Keynesian economics is based on theories, not verifiable facts. Moreover, Lord Keynes wrote the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money during the Great Depression, a worldwide event that traumatized tens of millions. It can fairly be said that the General Theory was a work heavily influenced by the highly unusual economic conditions of the times.

It is also more than a little unclear whether the Great Depression was the result of a failure of markets or a failure of government policy, although the General Theory appears to assume the former. Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, Penguin Press 2009, is a fascinating read about the CENTRAL bankers who arrogantly believed they could guide monetary policy for the benefit of their respective economies. The book won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for History. Likewise, there is also some question as to whether Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policies helped end the Great Depression or exacerbated and extended it (See the Cato excerpt at the end of this article. Although you might want to ignore the political undertones and just read it for the historical data presented).

Keynesian economics is dominant among public policy makers currently, but it does not stand alone as a theory of how economies work (or don’t work as the case may be). The Austrian school of economics, for instance, puts forth very different theories of how an economy works. “The Austrian School believes that the subjective choices of individuals underlie all economic phenomena. Austrians seek to understand the observed economy by examining the social ramifications of such individual choice. This approach, termed methodological individualism, differs significantly from many other schools of economic thought, which have placed less importance on individual knowledge, time, expectation, and other subjective factors and focused instead on aggregate variables, equilibrium analysis, and the consideration of societal groups rather than individuals.[13],” Wikipedia

Personally I think Kahneman and Tversky would find much to like in the Austrian School’s focus on the subjective choices of individuals as the foundation of all economic phenoma given that, Kahneman and Tversky did notable work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making, behavioral economics and hedonic psychology, and established a cognitive basis for common human errors which arise from heuristics and biases (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973; Kahneman, Slovic & Tversky, 1982; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

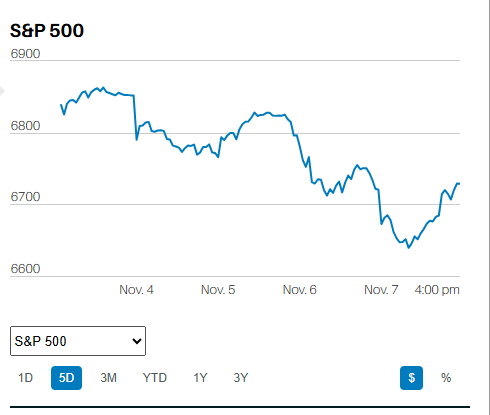

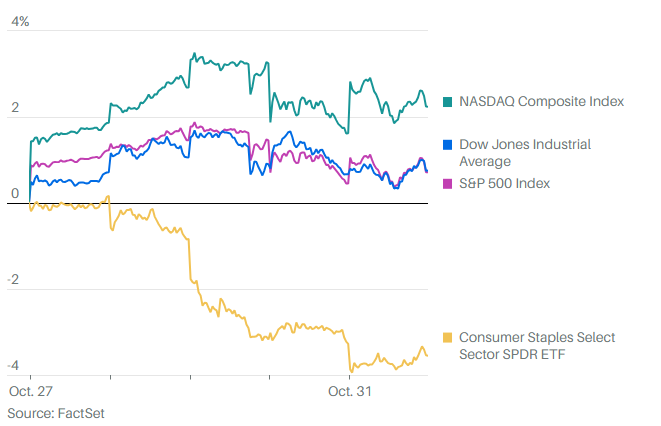

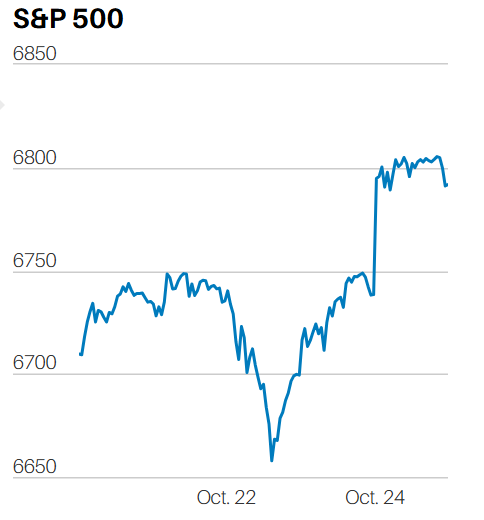

Regardless, the point is that Economics is not, never has been, and perhaps never will be a science in the “hard” sense. Nor do economists or public policy makers have the knowledge or even the necessary data to “fine-tune” or proactively manage the American economy. The idea that the Federal Reserve can taper its way out of Quantitative Easing without unintended negative consequences is closely held by the U.S. stock market for the time being. Yet it is far more likely that the Federal Reserve will continue to taper until bad stuff starts happening again…and then back pedal furiously as it opens the spigots once more in an effort to save the day.

The Fed’s ability to keep order in both the economy and markets requires energy, apparently in ever increasing quantities based on the observable trends. But the Second Law of Thermodynamics is unlikely to be denied and the Federal Reserve’s attempt to thwart it unlikely to be successful.