YIKES!

INFLATION IS ALREADY BITING

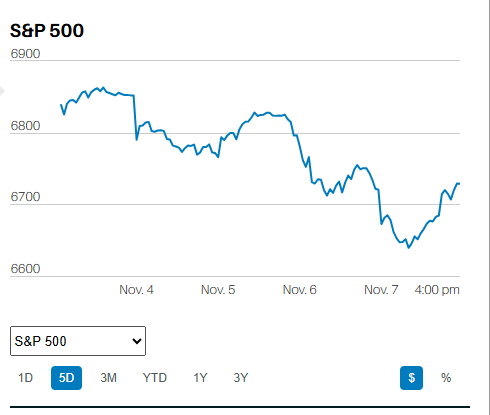

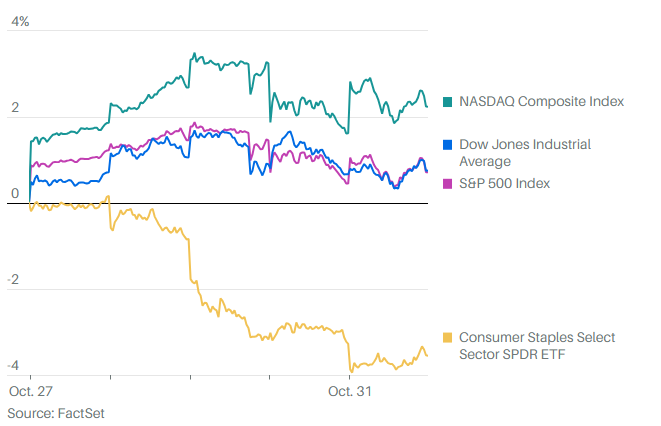

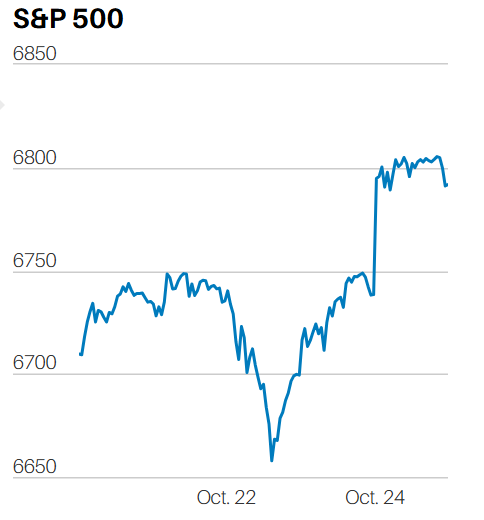

MARKET UPDATE

The market went up again. It’s getting boring, monotonous, and frankly, a little too one-way for my comfort. But, hey, the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, and ECB are now shoving $100 billion monthly into the financial system. The liquidity must go somewhere. Someone must hold the cash. How much cash does someone need though? Let’s buy, buy, buy assets with that cash. Stocks, bonds, real estate, commodities, and collectibles will return more than zero yielding cash, right? How much liquidity is $100 billion monthly? The world economy is around $85 trillion. One hundred billion monthly is $1.2 trillion annually or about 1.4% of economic activity worldwide. Except with a fractional reserve banking system in place in Japan, the EU, and the U.S. the potential for credit creation expands by a factor of ten. Cheap credit leads to all sorts of excesses eventually – think the internet and housing bubbles for instance.

Time to party like it’s 1999 because, hey, what could go wrong?

Officially the S&P 500 rose 0.7% to 3168.8 last week. It’s up about 26% on the year and around 54% over the past five years. It’s up about 188% over the last decade but only 102% since March of 2000. Doing a little math gives us 5.4% annually, excluding dividends, or about 7.4% with dividends since 2000. The very long-run real return for the S&P 500 is approximately 6.51% since 1871. Add back inflation of around 3.5% ( the post-World War II average) and you get the 10% long-run return that is commonly thrown around as the expected return for the stock market (often as if it were an inviolate birthright of all Americans smart enough to invest in stocks).

The major problem with plugging a 10% stock return into your retirement plan is that it’s only a long-run average and not the number you’re likely to experience during your retirement. Let’s back up and take a closer look at the 7.4% annual return (including dividends) that we’ve experienced over the last almost 20 years. Not bad but not 10%. Furthermore, we haven’t had a bear market in over 10 years. One is coming; we just don’t know exactly when. A run of the mill bear market will take the S&P 500 down by 20% to 30%. The last two bear markets saw declines of 50% or more; it took the market over five years to make back the losses from the last one. Pencil in a much more run of the mill 30% decline and, being generous, assume it starts from 3500 on the S&P 500 (10.5% higher than now). A 30% decline takes us down a very painful 1050 points on the S&P 500; all the way back to 2450 (which just happens to be fair value based on 2020 earnings estimates). By the time the S&P 500 falls to 2450, it’ll have only gained 56% since March of 2000. Pick a year (2020, 2021, 2022) and divide. Best case the market bottoms in 2020, giving the S&P 500 an annualized gain of 2.8% over twenty years. Using 2022 for the bottom gives you a 2.5% annual return since 2000. Throw in a 2% average dividend and you’re still only to 4.5%; nowhere near the 10% you were expecting.

Does anybody want to guess what’s happened to those poor folks who retired in 1999, the ones who based their retirement on earning 10% annually in the stock market? You might have seen a few of them greeting customers at Wal-Mart.

INFLATION IS ALREADY BITING

Inflation is a hidden tax on savers and creditors. Inflation transfers wealth to debtors. Retirees typically have social security as their only guaranteed source of income in retirement unless they use some of their retirement savings to purchase a low-cost fixed annuity. Of course, the guaranteed income from the annuity is only as good as the balance sheet of the insurance company that sold the annuity. It’s true that social security has a cost of living adjustment, but it’s also true that the COLA is not enough to keep up with real out-of-pocket inflation. Just ask someone who’s been collecting social security for twenty odd years and see what they say. There is no cost of living adjustment for private annuities.

All of this means that even mild inflation of 2% annually over a 20 to 25-year retirement is problematic. A 2% inflation rate is the equivalent of an almost 40% purchasing power decline in retirement over 20 years. Two percent happens to be the Federal Reserve’s goal these days. Long gone is the price stability mandate, or at least the mandate as we knew it. Now price stability equates to 2% annual price hikes.

Inflation has already been redefined by our government. It changed the yardstick back in 2007. No longer does it use the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which was designed to measure the actual cost of goods and services purchased by a typical American family. Now the Fed uses something called the Personal Consumption Expenditure Index (PCE). The thing to know about the PCE is that it runs consistently lower than the CPI. Whereas the PCE index has rested below 2% for most of the last decade and currently registers a mere 1.6%, the Atlanta Fed’s Sticky-Price CPI, which is a weighted basket of items that change price relatively slowly, is running at 2.8%. It’s been above 2% since mid-2014. The divergence in PCE and CPI largely can be explained by how healthcare and housing prices are treated, says Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at Bleakley Advisory Group in Fairfield, N.J.

The short explanation is that the PCE doesn’t use prices paid by consumers when measuring healthcare and housing. It uses Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates for healthcare, which are well below what consumers pay out of pocket. The PCE also uses imputed housing costs based on estimates of what a home would cost a renter, rather than actual home prices paid by actual homeowners. The upshot of all of this is that real inflation, the kind that impacts peoples pocketbook, is already likely above 2% and almost certainly destined to stay there for some time to come since the Fed announced last week that it intends to keep interest rates low until the PCE is above 2% for a sustained period. Yikes!

Regards,

Christopher R Norwood, CFA

Chief Market Strategist