Financial Advisor RED FLAGS

Market Update

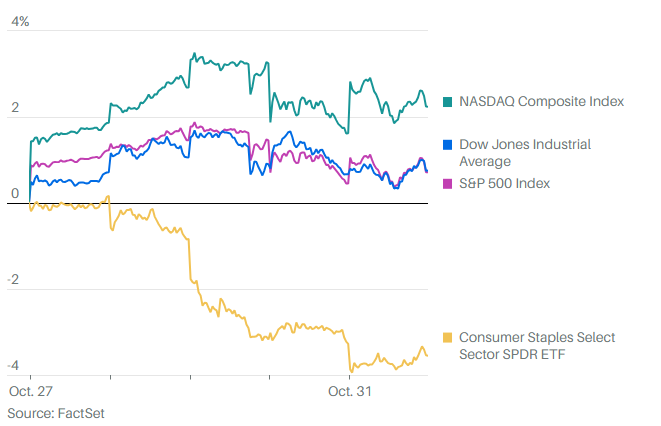

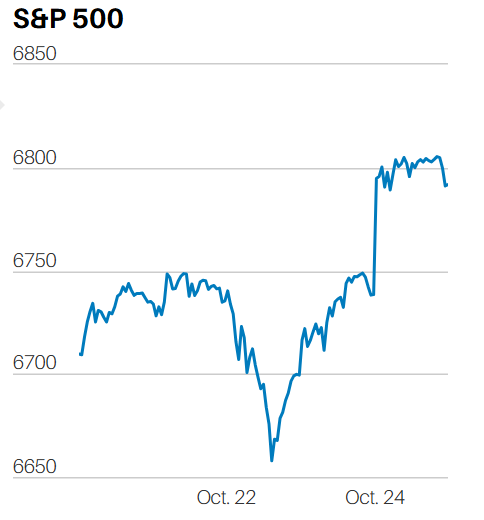

The S&P 500 lost 3.3% last week to close at 3924.26. The Nasdaq fell 4.2% and the Dow dropped 3.0%. the S&P is down 17% on the year. The Dow is down 13% and the Nasdaq is down 25%. The stock market is less expensive than at the start of 2022, but it still isn’t cheap. What's more, negative earnings revisions are higher than normal for the third quarter. Analysts have lowered S&P 500 earnings estimates by 5.4% in the first two months of Q3. The average decline for the first two months of a quarter has been 1.9% over the last five years, according to FactSet. Falling earnings estimates make the market more expensive.

The long-term and short-term trends are down. The 200-day moving average has been declining for 90 consecutive trading days. The odds favor a continued decline, according to Dean Christians of Sundial Capital Research. The S&P 500 has lost an average of 5.8% over six months after the 200-day MA declines 90 days in a row. Ninety consecutive declining days for the 200-day have occurred 23 times since 1930.

Eight market strategists recently polled by Barron’s provided an average target of 4185 for the S&P 500 by year-end. Individual estimates ranged from 3600 to 4800. It is a wide range given there are only four months left in the year. The wide range speaks to a high degree of uncertainty surrounding earnings and interest rates.

The S&P 500 has retraced 62.8% of its rally from the June low. The market bounced off that Fibonacci number on Thursday and Friday. It needs to hold the Fibonacci support in the coming week, or the odds favor a retest of the 17 June low. The 3636 June low is 7.3% away. Earnings estimates are falling. The Federal Reserve is tightening, and the technical picture is negative. The path of least resistance is still down.

Economic Indicators

Economic indicators last week show a slowly growing economy heading into the fall. The Chicago manufacturing PMI increased to 52.2 in August from 52.1 the prior month. The S&P U.S. manufacturing PMI was revised higher to 51.5 in August from an initial 51.3. Construction spending declined less in July falling 0.4% after falling 0.5% the prior month. ISM manufacturing in August held steady at 52.8%. Consumer confidence is improving. The consumer confidence index rose to 103.2 in August from 95.7 the prior month. Rising consumer confidence bodes well for the holiday shopping season. A negative, factory orders fell 1.0% in July after climbing 1.8% in June.

Leading indicators from prior weeks point to more slowing in the economy. A slowing economy should continue to reduce inflationary pressures. A reduction is needed. The headline numbers, both CPI and PCE, remain far too high. Negative productivity numbers and high unit labor costs spell trouble by adding to inflationary pressures and causing profit margin compression. Second quarter unit labor costs rose 10.2%. Companies can either eat the higher unit labor costs or raise prices.

As well, home prices are still rising rapidly. The latest S&P Case-Shiller U.S. Home price index showed an 18.0% increase year-over-year for June. It was down from a 19.9% increase the prior month. Rapidly rising home prices feed into inflation numbers, making a quick fall in inflation less likely.

The jobs market remained strong in August although jobs are a lagging indicator. Job openings rose to 11.2 million in June from 11.0 million the prior month. The Quits rate did fall to 4.2 million from 4.3 million. The Quits rate indicates how workers feel about the jobs market. A higher Quits rate indicates confidence in the ability to find another job.

Overall last week’s economic data continued to point to slow economic growth. It also pointed to sticky inflationary pressures. The Federal Reserve is in an unenviable position as we head into the last four months of the year.

Many Financial Advisors Don’t Earn Their Fees and Commissions

I’ve been associated with the financial advisor business since the mid-90s. That’s almost 30 years of watching and participating. One of the things I’ve come to believe is that most financial advisors don’t earn their fees. A second is that most financial advisors don’t provide much actual financial advice. A third is that many financial advisors know very little about investing. Those three things overlap of course.

I’m going to share parts of an email from a friend about a financial advisor meeting in which he participated. I’m also going to share some of my responses to his email.

My friend wrote at the start of his email, “You were right. Couldn’t really get a straight answer on most things.” One of the things he couldn’t get a straight answer on was how the advisor was compensated. The advisor was claiming that he was charging 1% on a $1.2 million portfolio (which is too much). The advisor told him that his compensation was capped at 1% even though he did use some loaded mutual funds and proprietary products. Companies make money from proprietary products. They incentivize their advisors to sell those products. It is unlikely the advisor is using loaded funds and proprietary products but not benefiting. My friend left the meeting uncertain about compensation. It is a red flag when an advisor has trouble explaining compensation.

Performance was another unsatisfying area of discussion. My friend wanted to see how the advisor’s recommendations were doing against appropriate benchmarks. The advisor’s response was that the investment choices were the clients. My friend wrote, “The biggest issue is that he wanted to stand behind the idea that these were Brian’s choices and as such don’t need to be measured against any type of performance benchmark.” There are a few things to unpack from that statement. First and foremost, it isn’t true. Brian is not making the choices when it comes to specific investments. The advisor is making those choices. And that leads to the second observation. Those choices should be compared to similar investments to determine if the advisor is adding value or not. You shouldn’t be paying an advisor for mutual fund selection unless those funds outperform.

The advisor also had this to say about benchmarking, “The benchmark is Brian’s goal of lifetime income.” More nonsense. Calculating total spending goals is part of financial planning. Benchmarking a portfolio is portfolio management. Benchmarking a portfolio is about measuring performance against alternatives. It isn't about determining lifetime spending goals. The advisor was giving a non-answer.

My friend also got the run around on asset allocation. Brian had about 9% of his portfolio in non-U.S. stocks. The advisor claimed he was not underinvested in non-U.S. stocks but didn’t provide a rationale to support that claim. In comparison Vanguard's 2030 target date fund has 40% of stock exposure in non-U.S. stocks. Fidelity's 2030 target date fund has 50% of stock exposure in non-U.S. stocks.

At one point in the conversation the advisor pinned the underexposure on his client. He claimed that it was Brian’s choice how much international stock he owned. One of an advisor's most important jobs is to help clients with asset allocations. An advisor who isn’t helping with asset allocations isn’t doing their job and shouldn’t be getting paid.

My friend also heard the typical double-speak when he asked about active management. Active management requires making decisions about what to own. Stock picking involves active management. Overweighting and underweighting different sectors and industries requires active management. The advisor’s response to questions about active management was, “we aren’t trying to time the market. I don’t know anyone who has successfully done that consistently.”

Of course, market timing is different than active management. Market timing involves being in the market or out of the market. The $1.2 million portfolio was full of actively managed mutual funds. Actively managed funds are trying to beat their benchmarks. It's why you pay more for them than for index funds. The advisor was saying that active management doesn’t work. He labeled it market timing. At the same time, he was using actively managed funds for Brian’s portfolio. Inconsistent to say the least. If active management equals market timing and market timing doesn’t work, then why is the advisor using actively managed mutual funds?

It's a sad commentary on our profession that individuals like this advisor are allowed to be financial advisors. The lack of competency is depressing yet all too common. Investors who use financial advisors should expect much more from them.

Regards,

Christopher R Norwood, CFA

Chief Market Strategist