BOND INVESTING

The stock market is going to lose 30% to 50% of its value at some point in the next five years or so.

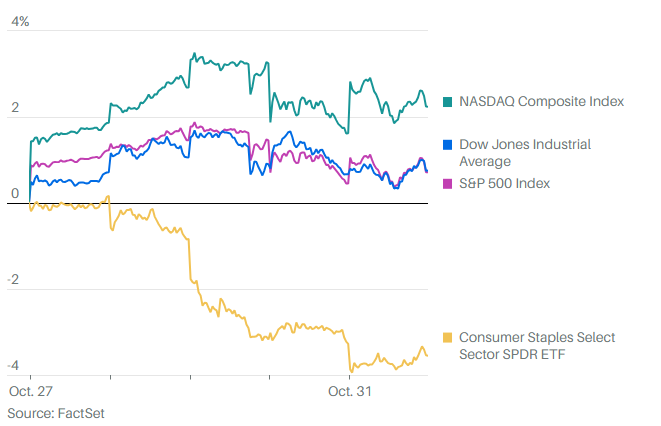

The probability of that happening is quite high. The U.S. stock market typically experiences a down cycle (bear market) when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates. Interest rates are the cost of money. When the cost of money goes up the economy slows down. When an economy slows down, business earnings grow less rapidly, or even fall. When business earnings grow less rapidly, or fall, stocks tend to drop.

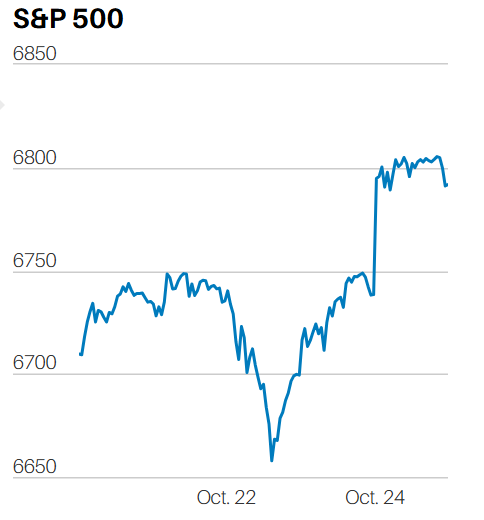

The stock market is currently high risk, not only because the cost of money is going up, but also because it’s overvalued. The market is overvalued because it’s been going up for nine years, rising around 300% since its 2009 low. The underlying businesses have not increased in value by 300%, or anywhere close to that amount, whether measuring the increase in value using earnings, book value, sales, or any number of other valid metrics. Most big companies don’t grow their business value quickly, certainly not by 300% over a nine-year period.

Many will argue that it isn’t possible to identify an overvalued market. Of course, they will often go on to say, almost in the same breath, that clearly the stock market was undervalued at its March 2009 lows. The incongruity of those juxtaposed statements seems to escape them entirely. They make the undervalued-at-its-lows argument to justify the nine-year gains while simultaneously blithely claiming the impossibility of identifying an overvalued market.

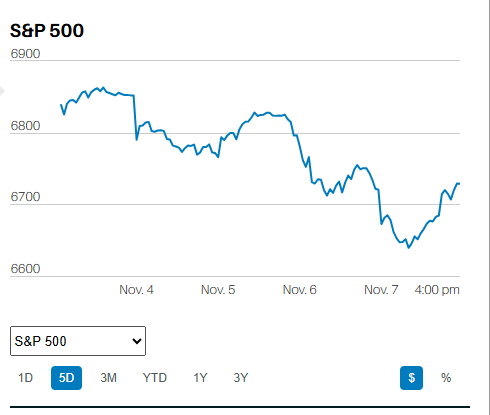

The fact is that we do have at least half a dozen metrics that have historically done a very nice job forecasting expected returns over 10-12 year periods. The current forecast is for an approximately 0% return over the next 12 years. Again, a high probability forecast. Why should we care that the S&P 500 is likely to earn nothing, or next to nothing, over the next 12 years?

Time; we should care because of time. The common refrain that you don’t lose anything in a bear market if you don’t sell is untrue. You always lose time. The S&P 500 didn’t return to its March 2000 highs until the fall of 2007. The S&P 500 didn’t regain its fall 2007 highs until the summer of 2013.

Time is plentiful and therefore cheap when you’re in your 20s. It is much less plentiful and much more expensive when you’re in your 50s and 60s. Time lost can jeopardize retirement goals, including one of your most important goals – your retirement date. Enter risk management.

Risk management is about recognizing when it is a high risk investing environment (as it is today) and gauging whether the next down cycle might force you to delay your retirement, or force you to change other, important retirement goals. Risk management has nothing to do with market timing and everything to do with attempting to minimize outcomes that might jeopardize retirement (spending) goals. Currently, anyone within 10-years or so of retirement should be scenario planning – looking at the impact of a down cycle sometime in the next five years, assessing whether it’s time to reallocate into a more conservative portfolio designed to preserve capital in order to preserve retirement goals.