DEBT FINANCED TAX CUTS DO NOT INCREASE ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE LONG RUN.

David Ricardo (1772-1823) theorized that it made no difference to the overall British economy whether the Napoleonic wars were financed by an increase in debt or by an increase in taxes. He theorized that the two were equivalent – the Ricardian Equivalency. (Hoisington Investment Management Q4 2017)

Dr. Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington looked at data from 1950 to 2016 and plotted the year-over-year percent change in real, per capita GDP against real, per capita Gross Federal Debt and found that:

“(The)… results align with Ricardo’s theory; although individual winners and losers may arise, a debt-financed tax cut will provide no net aggregate benefit to the macro-economy.” (Hoisington Q4 2017)

And from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): Only if the revenue losses are entirely offset by reductions in government consumption spending can the long-run drag on the economy be avoided,” Auerbach. (NBER Working Paper No. 9012),

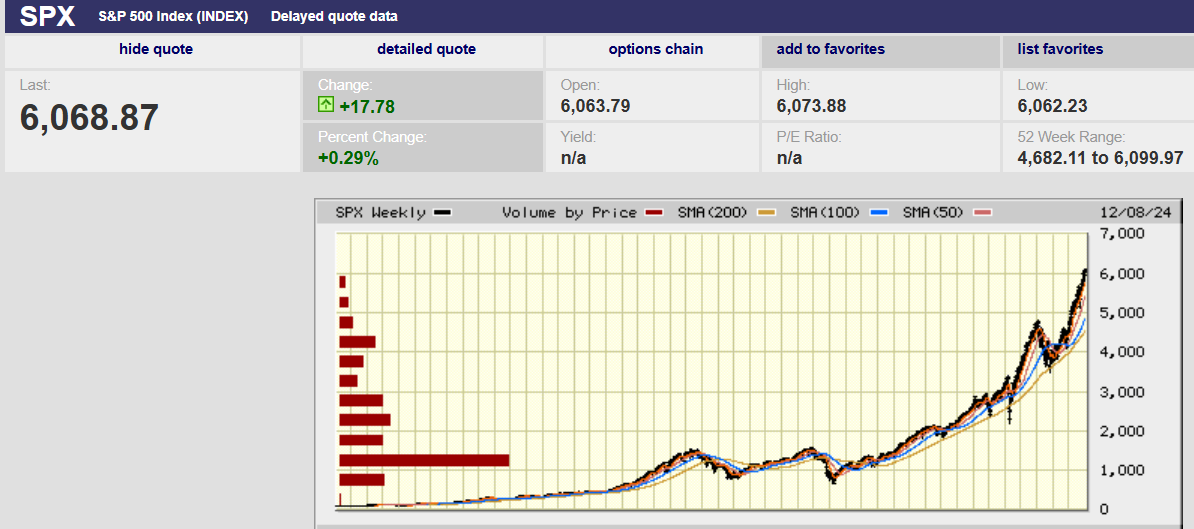

Importantly, investors are currently assuming that the Trump tax cuts will cause economic growth to accelerate in the coming quarters and provide a sustained increase in economic activity. The stock market is believed to be pricing in just such an economic acceleration. Should the economy fail to accelerate, as is likely, the stock market may well give back its pre-tax cut gains… at a minimum.

But why do debt-financed tax cuts result in no additional economic growth and perhaps even create a drag on the economy over the long run?

The GDP growth rate measures how fast the economy is growing. It does this by comparing current quarter GDP to the year-prior quarter. GDP measures the economic output of a nation.

Gross Domestic Product equals Consumer Spending plus Government Spending plus Investment plus Net Exports. Investment is spending by businesses on Capital Goods (assets such as buildings, machinery, equipment, vehicles, and technology). Capital Goods are used to produce goods and services for consumption. Net exports are exports minus imports.

A dollar spent by a consumer is worth the same amount of GDP as a dollar spent by government. Tax cuts don’t increase consumption when a dollar of tax revenue is returned to and spent by consumers rather than being spent by the government. There is a short-term increase in GDP if the dollar of returned tax revenue is spent by consumers, and government still spends a dollar, maintaining its pre-tax cut spending level by borrowing. The short-term increase in GDP is a result of increased borrowing, which pulls consumption forward. The acceleration in economic activity, if it occurs at all, is temporary, but the debt remains until it is repaid, even after the economy has slowed back to the long-run growth trend line.

Worse still, increases in borrowing result in a decrease in national savings, which does create a long-term drag on the economy. The drag results from a decrease in investment, which is necessary to spur productivity increases. Investment can’t occur without savings because, without savings, there aren’t any dollars available to invest. A decrease in investment means a decrease in capital accumulation. Capital accumulation is investment in plant, equipment, and technology, and is necessary for gains in productivity. Productivity increases are necessary for real GDP growth. Therefore, countries wishing to grow faster should direct more dollars to Investment and fewer dollars to consumer and government spending.

A tax cut doesn’t increase Investment if it doesn’t increase national savings. A nation must increase savings if it is to increase investment in capital goods and thereby increase productivity. Increased productivity, along with growth in the labor force, increases real economic growth rates.

The data and logic argue against debt-financed tax cuts if the goal is a sustained increase in economic growth rates.