THERE ARE EARLY SIGNS OF INFLATION

SUNNY SKIES IN 2020?

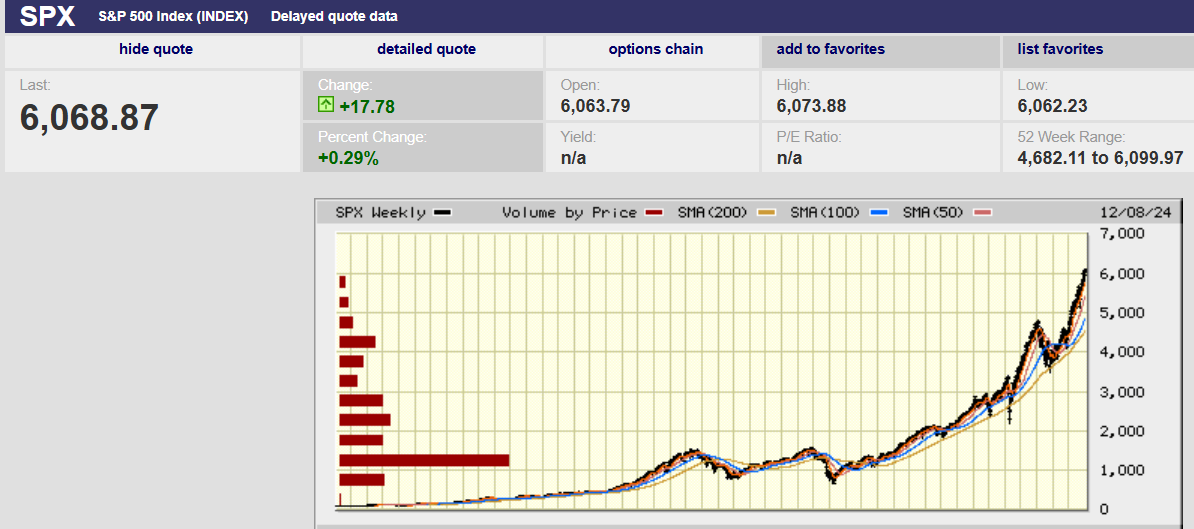

MARKET UPDATE

The S&P 500 rose 0.6% to 3240.02 last week and is up 29% on the year. The S&P now trades at 18.3 times 2020 forecast earnings of $177.88, up from 15.6 times earnings last year. The long-run average Price-to-Earnings multiple is 14.4 times, which would put the S&P 500 at 2561 or about 21% lower. Of course, interest rates are low, and investors seem willing to own a more expensive stock market when that’s the case.

However, how much longer interest rates will stay low is an open question. There are early signs of inflation perking up. The five-year trend in core inflation (subtracting food and energy prices) is at a five-year high, while small companies are planning to increase worker’s wages by the most in 30 years, according to Barron’s. Wage push inflation is a particularly insidious threat to price stability as it’s proved hard to stamp out in the past. Should wage inflation really take hold, the Federal Reserve will be forced to raise interest rates aggressively to stamp it out. Rising interest rates will result in both falling bond and stock prices. Of course, the tricky part is figuring out if and, as importantly, when wage inflation might kick off an interest rate tightening cycle.

It’s not comforting that almost everyone who’s anyone in the investing world is predicting low inflation for years to come. Currently, the five-year breakeven inflation rate for Treasury Inflation-Protected bonds is a mere 1.64% while the ten-year is at only 1.73%. In other words, professional money managers expect inflation to average only 1.73% in the decade to come; an expectation that almost certainly won’t be met given how determined the Central Banks of the world are to spark inflation.

Wage inflation also impacts corporate profitability, another threat to the U.S. stock market in the next few years. The S&P 500 is currently experiencing record profit margins with companies earning 14 cents on every dollar of sales. Net profit margins just happen to be one of the most mean-reverting of all the financial ratios. Econ 101 teaches us that excess profits are competed away in a capitalist economy as competitors zero in on companies who’re earning excess profits. Another threat to record profit margins is wage growth, which at 3.1% is the strongest it’s been since the last recession, according to Goldman Sachs. Unemployment is still at 50-year lows in the U.S.; it’s reasonable to assume that workers will continue to experience better wage growth as a result of more bargaining power.

It might already be happening. One government data set, which uses tax filings, shows that profitability has declined every year since 2013. Some of the decline is due to rising wages. The per-unit cost of labor has climbed faster than other costs for U.S. nonfinancial companies, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data.

In short, 2020 profit estimates are likely too high. A market pullback next year due to shrinking profit margins is a real possibility, even though many investors don’t seem to expect anything but sunny skies ahead.

Regards,

Christopher R Norwood, CFA

Chief Market Strategist