MARKET UPDATES, MARKET RISK, AND INVESTING

MARKET UPDATE

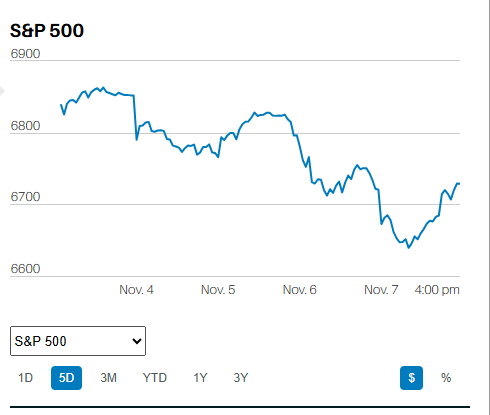

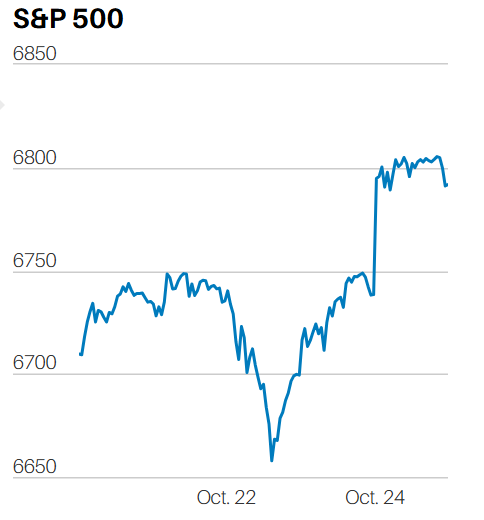

The S&P 500 held support at the 50-day moving average Tuesday, and again on Wednesday, before finishing basically flat on the week. The index couldn’t take out its Monday high around 2675 and there’s likely more resistance all the way up to 2800. The 200-moving average sits at 2745ish. What is resistance anyway? It’s where numerous transactions occurred in the past above the current price. What makes that resistance? Human nature. We have many biases that permeate our decision making. One of which is remembering the price paid for a stock or index, and incorporating that price into our decision making: “I paid $20 for it, and don’t want to sell at $15 and take a loss. I’ll just wait until it’s close to $20 again.” Voila! Resistance.

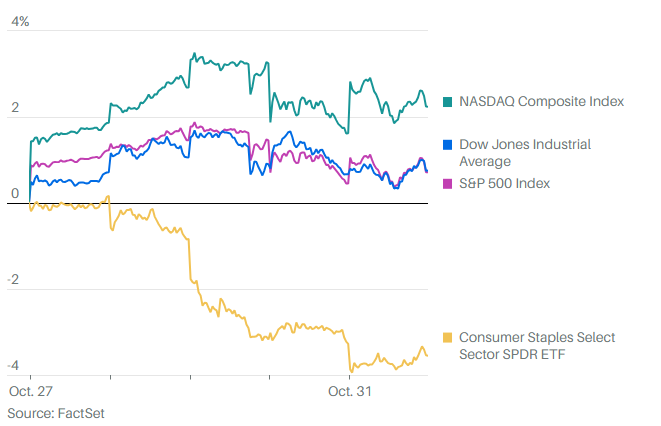

Reasons given by the pundits for a pause in the five-week-old rally were various, including supposed trouble with the Chinese trade negotiations and alleged bad news out of the economic summit at Davos. On the other side of the ledger was the supposedly more dovish talk from the Federal Reserve. Valid reasons for explaining why the market traded sideways last week? Perhaps, but probably not. Just to illustrate the absurdity of the blame/credit game – the end to the government shutdown was offered as both good news and bad news. The “bad news folks” are claiming that the end of the shutdown removes one uncertainty for the Federal Reserve, making it more likely they will continue rate hikes and shrink their balance sheet. This is usually bad news for the stock market, even though an end to the shutdown is obviously good for the country and the economy. The Fed Funds Futures market is beginning to price in a Fed rate cut in early 2020, an indication that the bond market is starting to sniff out a recession. Also, earnings estimates have fallen from 10% growth in September to 6% growth currently. Remember, over the long run it is earnings growth and interest rates that drive the stock market.

THE ERROR IN TRACKING ERROR

As pointed out a few weeks ago, Standard and Poor released its updated SPIVA report and the news wasn’t good for actively managed mutual funds – this is always the case. The data is pretty overwhelming that actively managed funds can’t beat their unmanaged index benchmarks after fees and other expenses. Perhaps it’s because they aren’t really trying.

Tracking error is the difference between a portfolio's returns and the benchmark or index it was meant to mimic or beat. Tracking error is sometimes called active risk. Mutual fund managers are typically tightly constrained in how much active risk they are allowed to maintain in their portfolios. A large-cap value stock mutual fund that is tasked with beating the Russell 1000 Value Index will hew closely to the holdings in the index for fear of introducing too much tracking error. However, they do need to make some active bets or they’re nothing more than an expensive index fund in disguise - an all too common occurrence, unfortunately. The focus on their benchmark leads to a thought process that would be foreign to many individual investors. You can hear an active manager (and I have) telling a colleague that he’s short Amazon, that it’s his biggest active bet currently. Shorting, of course, is the practice of borrowing and selling a stock you don’t own hoping to buy it back later at a lower price for a profit. One might conclude from the portfolio manager’s statement that he’s done exactly that – borrowed Amazon stock and sold it short hoping to buy it back later. In fact, what he actually means is that his portfolio has a smaller percentage dedicated to Amazon than the underlying benchmark. Perhaps his portfolio has a 1% weighting in Amazon, whereas the Russell 1000 index may have a 2.2% weighting. His active bet is to be underweight (short) Amazon by 1.2% of his portfolio; a very aggressive bet indeed for an active money manager these days, and a very plausible explanation for why active management in the mutual fund industry doesn’t add sufficient value to cover its costs. You have to actually try to beat the index if you want to beat the index. Managing business risk (money fleeing an underperforming mutual fund) isn’t a winning strategy.

Regards,

Christopher Norwood, CFA

Chief Investment Officer