MARKET UPDATE AND INVESTING

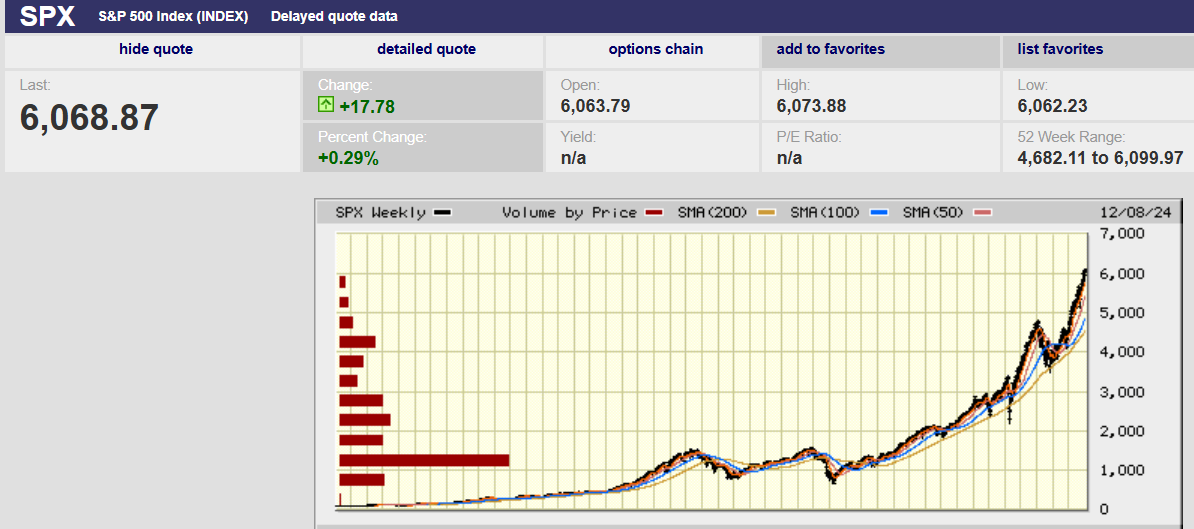

MARKET UPDATE

On Wednesday the Federal Reserve signaled that rate hikes are on hold, and also indicated it might adjust the rate of balance sheet shrinkage. Currently, the Fed is reducing its balance sheet by $50 billion monthly, or $600 billion annually. A shrinking balance sheet has been estimated to equal at least two additional rate hikes already. The impact on the cost of money might be even greater. According to Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca of the Council On Foreign Relations, one analysis has the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet runoff equaling 2.2% in additional rate hikes by year-end 2019 at the current pace.

If correct, the cost of money has risen substantially more already than indicated by the Federal Funds rate hikes, and the impact on the economy will likely be greater than many are anticipating.

Nevertheless, investors reacted to the dovish talk by pushing the S&P 500 decisively through 2670, where the index had stalled twice a week prior. The S&P 500 finished Friday at 2706.56, up 1.6% on the week. The relief rally (still most likely) is now 26 trading days old. The Fed has given it new life with its apparent monetary policy change; however, the expected economic slowdown might be more severe than many believe. A heavily indebted economy is less able to deal with the tightening that’s already occurred, both directly with rate hikes and indirectly with balance sheet shrinkage.

Earnings estimates are falling. Analysts forecasted a 10% rise in 2019 earnings last fall, but are now looking for less than 6% earnings growth. A growing number of analysts are expecting negative corporate earnings growth in the first quarter of 2019. Pricing power in the U.S. in the fourth quarter of 2018 was weakening. “Based on such diverse items as transportation, apparel, and commodities, price weakness was widespread in the fourth quarter, suggesting final demand is weak relative to productive capacity,” writes Dr. Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management. He goes on to write: “Exports, vehicle sales, and home sales exhibited characteristics of sectors in recession.”

Stock investors may be right in bidding up the S&P 500, but we think it increasingly likely that the U.S. economy is in for a pronounced slowdown. We are in line with Mike Wilson, Chief Equity Strategist for Morgan Stanley, who is currently recommending that investors wait to buy until the relief rally ends and stocks, once again, move lower. Of course, that also applies to individual stocks, which means we buy when we find a good company on sale, regardless of what the overall market is doing.

INVESTING

The only risk-free investment is U.S. Treasuries. U.S. Treasuries currently yield 2.42% at the short end, and 3.03% at the long end. It’s not possible to earn more than the U.S. Treasury yield, at any given maturity, risk-free. Nor is it currently possible to earn more than 2.42% in a 3-month investment or more than 3.03% in a 30-year investment. Any investment with an expected return above the risk-free rate has risk. Corporate (AA) bonds currently yield between 2.01% and 4.59%. Corporate bonds have credit risk – the risk of default. The S&P 500 returned 5.52% in the 20 years ending 31 December 2018, well below its historical return of about 9.5%. The 5.52% annualized return includes the current bull market returns of 2009-2018. It’s an almost guarantee that the 20-year trailing S&P 500 returns will be lower than 5.52% at the bottom of the next bear market. Investors need to adjust their expectations. Retirement plans assuming 8% - 10% portfolio returns over the next 10 years will almost certainly disappoint. Mike Wilson of Morgan Stanley is forecasting S&P 500 returns in the mid-single digits for the next 10 years. We think he may prove overly optimistic. What to do? Save more and use realistic return assumptions in your retirement planning.